In the Dead of Winter - Part I

With several feet of snow on the ground and another storm churning down on us it's hard not to think about snow and ice. A small brook runs through our backyard here in Amesbury and just before the freeze this year the brook flooded. My children declared it a skating rink and as they slid and slipped on the frozen surface I found myself thinking of the body of water which captivated me as a kid, Lake Gardner.

I grew up in Amesbury and after graduating from Amesbury High, moved to attend school at UMASS Amherst. After several more moves for graduate school and work, my husband and I found ourselves in D.C. with a newborn and in need of some family support. We packed up and headed North with little in the way of a plan. Luckily my parents rented us an apartment in my childhood home atop a small hill adjacent to the much larger Po Hill. From their third floor apartment the view of Lake Gardner below is picturesque. I remember as a kid being fascinated by the straight lines of the lake's edges and marveling at the right angles where the shorelines meet. I must have been about 9 years old when my father let me in on the secret that the lake was manmade. It wasn't until I moved back to Amesbury and found the lake my neighbor once again that I began to wonder about the history of the water there and what purposes it served for the city.

Many will be familiar with the story but for me it was a new discovery. In 1871 the Salisbury Mills Company acquired the rights to flood the plains surrounding the Powow river by way of a dam. In 1872 the job was done, the dam complete and the "pond" was here to stay.

The lake quickly became integral to daily life of the town's inhabitants. Farmers secured watering rights for livestock and the energy from the falls powered the factories downstream. But what happened in the winter? As a child I could see the ice fishermen making their determined and frosty trek to the lake's center, and cross country skiers gliding along the untouched snow cover. Idyllic certainly, but it wasn't always a winter recreation spot. Until the middle of the 20th century Lake Gardner was, like many a New England pond, a source for the robust ice harvest industry. Where there are now homes lining Whitehall Road there were once ice houses, huge wooden structures designed to store the large blocks of harvested ice and keep it cool throughout the hazy and hot summer months.

It took very little time for the ice companies to take up residence on the lake and the two major companies in operation as early as 1875 and through the early years of the twentieth century were Joseph Pray's operation and H.H. Bean and Sons. The former operated for the longest period although the company passed hands over the years. The business came to be known as Lake Gardner Ice Company and in 1909 the owner Frank Currier sold the business to Roy H. Locke. Lake Gardner Ice worked out of five ice houses on the West side of the lake. You can see four of them in the image below.

R.H. Locke's ice houses lining the western shore of Lake Gardner. Image courtesy the Sara Locke Redford Papers, Local History Collection, Amesbury Public Library.

By the time Locke became a Lake Gardner ice-man in 1909 the business of natural ice harvesting was a century old. Although wealthy families in Europe had stored ice in underground houses (much like caves) for decades the commercialization and ultimate success of above ground ice storage was an American story, and a Yankee one at that.

Frederic Tudor, a Bostonian from a wealthy family, shipped his first load of New England ice to the West Indies in 1806. He was familiar with ice storage because his family’s country estate, Rockwood, was equipped with its own ice house situated on the edge of their small pond located then in Lynn (now Nahant) Massachusetts. His success, however, was far from inevitable. Tudor’s business peaked and plummeted throughout the 19th century because of his own financial missteps combined with unavoidable shipping restrictions brought about by the wars.

Ultimately, his persistence paid off and he popularized ice as a commodity throughout the southern United States and the tropics. Ice cream and chilled cocktails (mint juleps became particularly popular) gained great popularity and ice established its place as a staple in many American homes. Tudor's firm is credited with innovations involving refining methods for stacking the large ice blocks in the houses and identifying an efficient insulation method for the ice, sawdust.

Reports describe a particularly robust Amesbury harvest in 1906 of about 50,000 tons which were destined for a Boston operation to be distributed up and down the Eastern coast and possibly even abroad. Some sources suggest that much of this harvest was done after daylight hours to avoid the inevitable melting of the ice. The image of the houses alive with workers in the frigid and dark night is captivating.

According to Amesbury historian Sara Redford, Locke’s five ice houses were able to accommodate up to 10,000 tons of ice when fully stocked. The buildings were packed, the ice covered with sawdust (or hay in some instances) for insulation. An 1892 publication, The Ice Crop: how to harvest, store, ship and use ice, a complete practical treatise, suggests a 12 inch layer of sawdust between tiers of ice blocks to ensure optimal insulation. Once fully packed the entrances were nailed tightly shut until the summer months demanded distribution. Ice house construction included sophisticated drainage and ventilation systems and typically the houses had several doors on either end. The ice would enter on one end, the lake side, and was dispensed from the street side. Amesbury residents would have been the primary market but households and businesses from surrounding towns received deliveries as well.

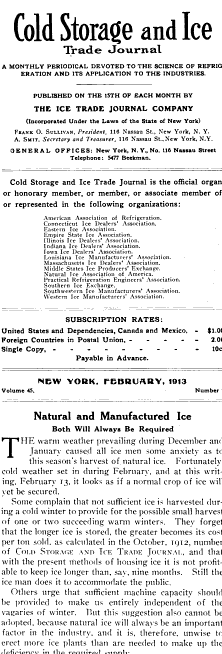

Several publications were dedicated to the ice trade and a 1913 edition of Cold Storage and Ice Trade Journal indicates that ice yields varied significantly from year to year and ice harvested during a particularly productive year could survive in storage for several seasons. The first couple decades of the 20th century marked a unique time when manufactured ice operations competed with the natural harvest. That relationship is discussed in “Natural and Manufactured Ice” in the February, 1913, issue of Cold Storage and Ice Trade Journal.

Locke ran Lake Gardner Ice Company until his death in 1930 by which time electric refrigeration was increasingly common and the profits from the company were dwindling. In 1947 fire subsumed the ice houses once again, previous fires had destroyed earlier versions of the barns in 1913, and the structures were not rebuilt.

The frozen water trade required workers to keep the lake clear of snow to maintain access to the ice underneath. At this time of year a century ago the lake would be buzzing with ice workers sweeping and scraping the flakes in preparation for the next cutting and racing to prepare the surface in advance of the next storm. As fascinated as I am by the process I'm grateful to be inside my warm house today with the intermittent clattering of my refrigerator's ice maker for company.